Why EU deal is better for farmers than one with US

An FTA with the European Union that includes agriculture can be beneficial for India in products where it has strong export interests. Agriculture has been a major stumbling block in the still-to-be concluded free trade agreement (FTA) between India and the United States (US). The politically sensitive sector is expected to be off the table even in the “mother of all deals” that India is set to finalise with the European Union (EU) this week.

There are two key reasons why India wants to exclude agriculture from any FTA that opens up its markets to imports through duty reductions and dismantling of non-tariff barriers.The first has to do with livelihoods.

The US has just 1.88 million farms, as per the most recent survey in 2024, while it was 9.07 million for the EU in 2020. The last Agriculture Census in 2015-16 for India, on the other hand, placed the total operational holdings at 146.45 million. The number of land-holding farmer families benefiting from the Narendra Modi government’s PM-Kisan Samman Nidhi income support scheme alone stood at 97.14 million during the April-July 2025 instalment round.

Given the large population deriving its livelihood from farming, successive Indian governments have been cautious about granting greater market access to foreign produce. Significantly, an interim trade agreement that even the EU signed on January 17 with four Mercosur countries – Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay – was dealt a blow in the European Parliament.

On January 21, the 27-country bloc’s lawmakers voted 334 to 324 to refer the trade deal to the European Court of Justice. It followed protests, especially in France, by farmers who claimed that the FTA would lead to a surge in imports of beef, sugar and poultry products from the South American nations.

The second issue pertains to subsidies given to agriculture producers.

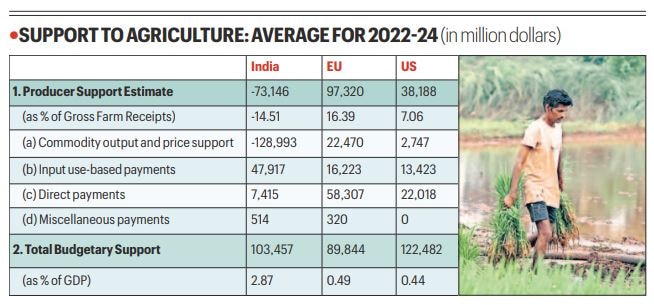

The accompanying table shows the so-called Producer Support Estimate (PSE) – the annual monetary value of gross transfers from taxpayers and consumers to the farmers of a country. This averaged $97.3 billion for the EU during the three years ended 2024 and was equal to 16.4% of gross farm receipts, i.e. the total value of agricultural production at the farm gate, inclusive of market revenues as well as budgetary support payments.

The PSE covers both government payments to farmers, whether in the form of direct income transfers or input subsidies, and commodity market price support. The latter arises from policies that create a gap between domestic market prices and international “border” prices of individual agricultural commodities, measured at the farm gate level.

According to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the EU countries extended an average annual support of $58.6 billion to their farmers during 2022-24 only through direct and miscellaneous payments. Another $16.2 billion worth of support was provided by way of subsidy on inputs used in agriculture.

The balance $22.5 billion support came via government policy measures that raised domestic farm gate prices of agricultural commodities above their corresponding border (import parity) prices after deducting inland transport, handling & storage and distribution costs. This amount basically represented a subsidy or transfer from EU’s consumers to farmers, with the former paying more than what it would have otherwise cost to import the particular commodity.

The average annual PSE for US farmers, likewise, worked out to $38.2 billion or 7.1% of gross receipts during 2022-24. That included $22 billion of direct payments, $13.4 billion of input subsidies and $2.7 billion of commodity output market price support.

Where India stands

India’s case is interesting.

The aggregate subsidies on inputs used for agriculture – be it fertilisers, electricity, irrigation water, credit or farm machinery – averaged $47.9 billion in 2022-24. That was higher than for any of the 54 countries monitored by the OECD. However, direct income support and miscellaneous payments to farmers in India through schemes such as PM-Kisan, at $7.9 billion, were way lower than that by EU ($58.6 billion) and US ($22 billion).

Even more revealing is commodity market price support, the annual average value of which was estimated at a staggering minus $129 billion for India during 2022-24. The various domestic stocking, movement and marketing restrictions on agricultural commodities, on top of export curbs imposed from time to time, have the effect of depressing farm gate prices in India below their corresponding border (export parity) prices after deducting inland transportation and other charges.

The negative commodity price support of $129 billion – implying a net taxation of Indian farmers – more than offset the input subsidies of $47.9 billion and direct payments of $7.9 billion. As a result, India had the most negative agriculture PSE of $73.1 billion, equal to minus 14.5% of gross farm receipts, among all countries in 2022-24. While the total taxpayer-funded budgetary support for Indian agriculture was higher as a percentage of GDP (2.9) than that for the EU (0.5) and US (0.4), the net taxation of its farmers from suppressed prices was estimated even higher.

It is instructive to note here that China heavily subsidises its farmers. Its PSE of $270.5 billion (13.3% of gross farm receipts) in 2022-24 was, indeed, higher than for any country, comprising $202.1 billion of commodity output price market support, $17.9 billion of input subsidies and $50.6 billion of direct payments. China, unlike India, does not seem to net tax its farmers.

India’s EU farm strategy

Ashok Gulati, distinguished professor at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, feels that the threat of farm imports from the EU is not as much as from the US.

An FTA with the US can potentially lead to substantial imports of American corn, soyabean, ethanol and cotton into India. The EU, by contrast, isn’t very cost competitive in most agri-commodities, barring maybe cheese.

“Even there, they may want to only supply premium cheese such as Gouda from the Netherlands. Apart from that, there could be imports of wine, spirits or olive oil that wouldn’t really hurt Indian farmers,” says Gulati.

An FTA with the EU that includes agriculture can actually be beneficial for India in products where it has strong export interests – like seafood, fruits and vegetables, beverages, spices and rice.

In 2024-25 (April-March), India exported shrimps and prawns valued at $518.16 million, cuttlefish and squids ($361.79 million), coffee ($775 million), tea ($93.57 million), grapes ($175.5 million), rice ($279.34 million), sesamum seeds ($77.66 million), dried onion ($75.33 million), cucumbers and gherkins ($57.86 million), cumin ($59.47 million) and turmeric ($36.82 million) to the EU. These weren’t small.

Simply put, Indian farmers have less to fear from a deal with the EU than with the US. “If necessary, we can levy a 15% sterilisation duty to neutralise the subsidies that they are giving to their farmers. That should be adequate protection against imports,” adds Gulati.

Source : Dairynews7x7 Jan 26th Indian express by Harish Damodaran